A Guide for Physicians

and Other Healthcare Providers

Listening to Patients

Case Report...

A 58 year-old female former smoker began noticing increasing shortness of breath over a 1-2 year period. She went to her usual doctor who found no abnormalities other than possible COPD (emphysema or chronic bronchitis). He gave her an albuterol inhaler, which didn’t really help much. Her dyspnea gradually but rapidly worsened and became very noticeable to her friends and coworkers over the next 6-8 months. She became cyanotic and severely dyspneic just walking into her workplace from her car. She required high amounts of oxygen to maintain an adequate amount of O2 in her blood.

No one was listening to the patient...

She was referred to a pulmonologist and a cardiologist, but to no avail. The diagnosis of COPD was deemed the most likely cause despite the rapidity with which her symptoms developed and despite the fact that she had quit smoking 12 years before.

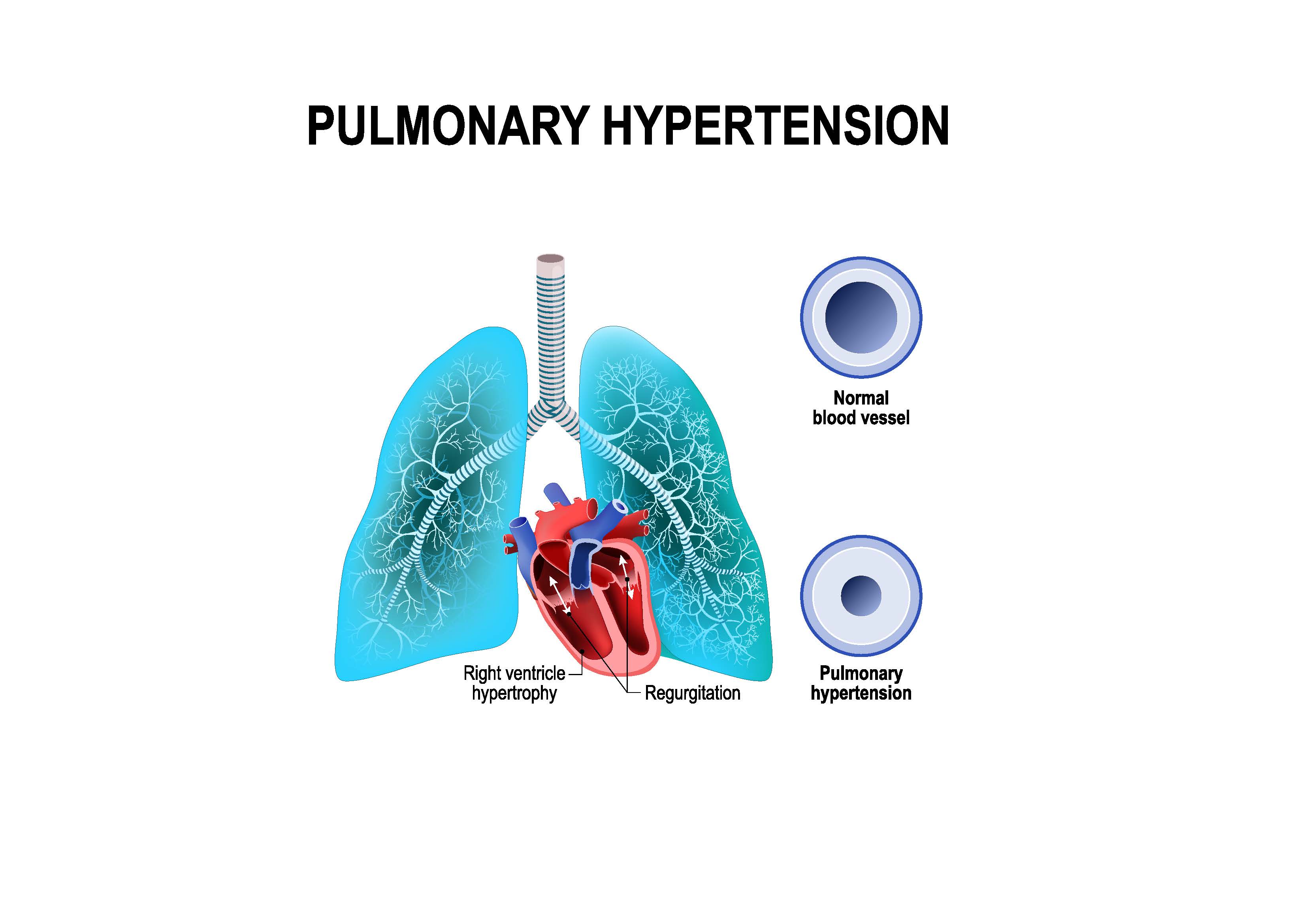

After telling her doctors repeatedly that something was wrong, she referred herself to a medical center where a cardiac catheterization was done, and she was found to have severe primary pulmonary hypertension.

Finally – a diagnosis that made sense, but sadly, one that had a very poor prognosis – usually only about 4 years, 2 of which had been wasted and untreated, because her local doctors did not listen to her, did not believe there was anything going on but the usual COPD which is common in smokers. Never mind that the course was different, that it was much more rapidly progressive than COPD.

After a brief trial of some oral medications, which didn’t help, she was started on a Prostacycline infusion. This is a rarely used powerful pulmonary artery vasodilator which can only be given intravenously and requires a battery-operated IV pump to be carried with the patient at all times. If the infusion stops, the patient immediately becomes hypoxic. If it is given too fast, systemic blood pressure will drop and cause hypotension and shock. She was specifically told that the IV line should never be flushed because too much of the prostacycline would get into her system too fast.

ER Experience...

She was warned about all of this at the medical center. So, a few months later when her pump stopped working due to a defective valve, she noticed the increase in shortness of breath right away. She went to the local emergency room and asked that they call the doctors at the medical center to find out what to do, which they did not do. She begged the ER doctor not to flush the IV line, which he did anyway, causing her considerable anxiety. Her blood pressure dropped like a rock and she became lightheaded immediately. Fortunately, her pressure responded to a large fluid bolus and she did not die, but she could have.

Then, after the fluid bolus, her bladder quickly filled. She asked the nurses several times to help her to the bathroom or to get a bedpan for her. 45min passed, during which time she heard the staff talking, laughing and joking just outside her room. She could not hold it any longer and finally got up to go to the bathroom herself. She was very lightheaded, but somehow made to the commode in time. Then she was reprimanded for trying to get up by herself.

The ER doctors had no idea how to fix her problem, so after she was released, she was driven by her daughter to the medical center 2 hours away. The doctors there found that the pump had a faulty valve. Once that was replaced, her pump worked fine again, and she was able to go home.

Fortunately, she survived that experience, but not without a lot of anxiety and consternation. She knew more about the potential effects of the medication than anyone in the ER, yet no one listened to her. Once she arrived in the ER, she lost total control of what happened to her. There was no consideration of her concerns. No attempt to call the doctors who knew about the medication and the pump. No help with basic body functions in a patient who had already become hypotensive while in their care.

Her course continued to worsen over the next year and she ultimately died at home in the loving care of her family.

The Moral...

Throughout the whole course of her illness, she kept asking me, her brother, “Why don’t doctors listen to their patients when they tell them something is wrong?”

I may be as guilty as her regular doctors, because I don’t think even I reacted to her symptoms appropriately in the beginning. I finally encouraged her to go to the medical center, but that was after many months of not listening well myself, telling her to keep going to her usual doctors and maybe they will figure it out.

We tend to think about the easy diagnoses, inside the box, and have to be pushed sometimes to reassess the situation when things are not following the usual course. We often don’t hear what we don’t want to hear, either because it causes too much work or too much heartache.

When our patients are saying, “Something is wrong”, make sure you are thinking about ALL the possibilities, not just the common ones. And when the patient knows more about their illness and their medications than you do, because of the rarity of the situation, make sure you listen to what they are saying so that you do not cause them more harm than good.

References:

Medline Plus: Pulmonary Hypertension

Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension: From Bench to Bedside

4 Essential Keys in Effective Communication

This page was last updated on July 20, 2019.

Back to "Home Page"

Disclaimer | Privacy Policy | Copyright | Sitemap | Contact | Comments

On this day of giving thanks, I am reminded of all of those who have supported this site over the years. I welcome your comments, your guest articles, and your readership. I am deeply grateful for all…

On this day of giving thanks, I am reminded of all of those who have supported this site over the years. I welcome your comments, your guest articles, and your readership. I am deeply grateful for all…